For people who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s, everyday life was harder, but it also taught them some important lessons. Since then, many of those habits and values have gone out of style, and they’ve been replaced by speed, ease, and always being connected. But they still affect how millions of parents (and now grandparents) see the world today.

A different kind of childhood

There were fewer safety nets and fewer shortcuts when I was a kid in the 1960s and 1970s. Parents worked a lot of hours. The kids walked to school. If you wanted something, you either waited, saved, or did without. There were strikes, inflation, and social tension during that time, so it wasn’t very romantic. However, it did give people a certain way of looking at life.

People who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s often learned a lot of useful skills, like patience, thrift, grit, and a strong sense of “we.”

TED talks and life-coaching slogans didn’t teach those skills. People picked them up in kitchens, on construction sites, on crowded buses, and in loud playgrounds. A lot of these lessons are fading away now, even though the problems they solve—anxiety, loneliness, and short attention spans—are becoming more obvious.

The worth of hard work

In a lot of Western homes at that time, kids were expected to help out. That could mean doing a paper round, putting things on shelves at the local store, or taking care of younger siblings. Most of the time, jobs were boring and hard, and the pay was low.

But those shifts after school or on Saturday mornings taught a simple rule: work hard first, then get paid.

For people born in the 1960s and 1970s, “hard work” was not a hashtag. It was necessary, and respect was earned, not given.

Psychologists now call this kind of steady work “grit,” which means the ability to stick with long-term goals. Research shows that teens who learn to keep going even when things are boring or hard are better able to handle problems as adults. It’s hard to teach that lesson in a culture where people expect things to be delivered the next day and get feedback right away.

Finding joy in simple things

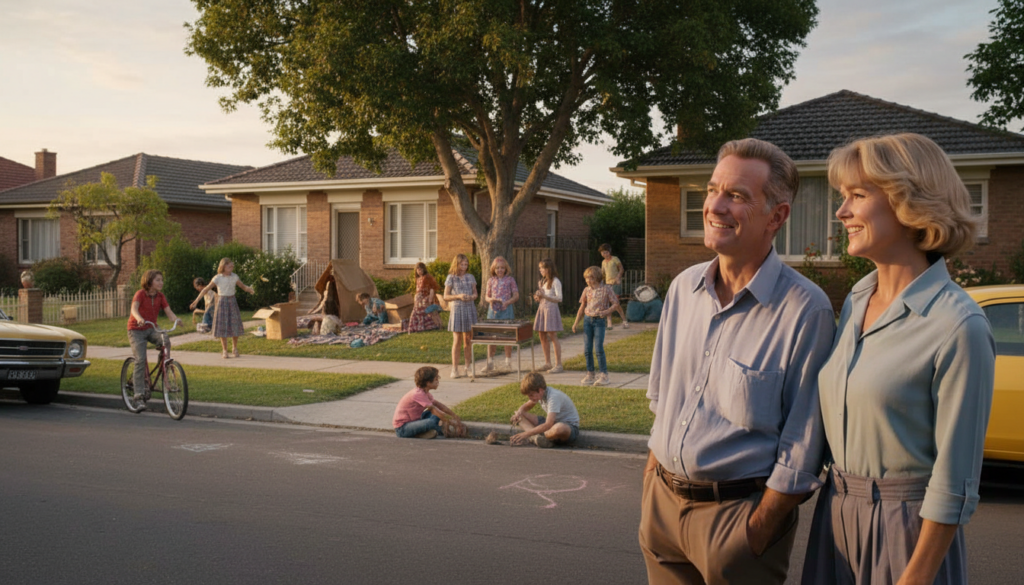

People who grew up during that time don’t usually start with expensive toys when you ask them what they remember. You hear about long summer nights outside, playing football in the street, making your own dens or all of you crowding around the one TV at home.

Riding a bike until the streetlights came on

Trading comics or records with friends

Board games that took up the whole Sunday afternoon

Instead of big parties in rented spaces, make your own birthday cakes.

At the time, those experiences didn’t seem special. They were just life. But they quietly reinforced the idea that happiness doesn’t always come with a receipt or a battery.

A lot of people who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s still think that happiness is more about who they’re with than what they own.

Economists now talk about “hedonic adaptation,” which means that people quickly get used to new things and then want more. The old habit of finding happiness in small, repetitive activities like eating together, going for a walk, or talking on the doorstep helps balance out that constant need for more.

The strength of community

There were also protests, marches, and social movements in the 1960s and 1970s. Street politics was loud, messy, and visible. It included civil rights, anti-war campaigns, and women’s liberation. People felt the need to work together through unions, churches, local clubs, and neighbourhood networks even in places that weren’t big cities.

Community wasn’t just a word on a company’s website; it was the neighbour who had a spare key and the street that kept an eye on your kids.

Many people left their doors unlocked. You knew who lived three houses away. People had to work together because they were all going through hard times, like blackouts and factory closures. Sociologists now say that this kind of “social capital” has gotten thinner because people are living more individualistic lives and only connecting online.

The skill of waiting

Before streaming and social media, waiting was a part of almost everything. You waited for the bus, for letters to come, for film photos to be developed, and for your favourite song to play on the radio. You missed the TV show if you didn’t see it.

That daily experience changed what people thought would happen. Not everything had to be fast, and not everything had to be.

Being patient was more of a normal thing than a good thing. There was frustration, but there was also a quiet acceptance that some things take time.

Interestingly, contemporary studies on children’s self-control indicate that the ability to postpone gratification has not deteriorated as significantly as nostalgia suggests. But adults who grew up with slower rhythms often feel out of place in a culture that sees every delay as a problem that needs to be solved by an app.

Unscheduled time with family

For many households, evenings and weekends revolved around the family by default. There were fewer after‑school clubs, fewer screens, and less pressure to be constantly busy. The result was a lot of unstructured, sometimes chaotic togetherness.

Dinner at the table gave children a daily chance to talk – or argue – with adults. Sunday visits to grandparents were routine, not a special event. Siblings were companions and, occasionally, rivals you could not block or mute.

People who grew up in the 60s and 70s often describe family moments not as perfect, but as steady – like a background rhythm that held everything together.

Modern studies now link regular family meals with better mental health, stronger literacy and fewer risky behaviours among teenagers. What older generations saw as ordinary might have been one of the most protective habits of their youth.

Learning resilience the hard way

The 60s and 70s were hardly gentle decades. Oil crises, unemployment, political scandals and cultural conflicts all filtered down into everyday life. Many families lived close to the edge financially. Holidays abroad were rare. Luxuries were postponed or never came.

Yet those pressures forced a kind of creativity: making do, repairing instead of replacing, leaning on extended family in tough times.

Resilience, for that generation, often meant adapting without fanfare – “just getting on with it” when things went wrong.

Psychologists now describe resilience as a mix of inner strength and outer support. The older model had both: strict expectations at home, but also neighbours, relatives and local institutions that stepped in when crises hit. That mix is harder to recreate when people feel both more isolated and more financially stretched.

Respect for nature and the outdoors

Another striking difference lies in how children met the natural world. For many in the 60s and 70s, fields, parks, streams and waste ground were daily playgrounds. You got dirty. You fell out of trees. You came home only when called – or when you were hungry.

Those hours outside built not only strong memories but a sense that humans are part of a larger landscape, not just users of it.

The generation raised outdoors often feels a sharper jolt when they see green space vanish or wildlife decline.

Today, paediatricians warn of “nature‑deficit” in children who rarely play outside. Evidence links outdoor time to better attention, stronger immunity and lower stress. The once‑normal childhood of wandering around outside now looks like a kind of low‑tech health intervention.

Authenticity before filters

The 60s and 70s also brought a surge of personal expression: long hair, bold clothes, protest music, and a questioning of rigid social roles. You could not edit a Polaroid or reword every sentence; you said things, sometimes badly, and lived with them.

That did not mean life was free of judgement, especially for women, minorities or LGBTQ+ people. Yet for many, those decades opened a path to living closer to their own values, even if that meant clashing with parents, employers or the media.

Authenticity then meant trying to align your life with what you believed, not curating a flawless version of yourself for strangers.

Today’s constant self‑presentation online can blur the line between performance and reality. Older generations often feel uneasy watching teenagers obsess over likes and filters, because they remember a time when embarrassment was local, not global, and identity felt less like a permanent broadcast.

What these lessons could mean now

Recreating the 60s and 70s is neither possible nor desirable. Few people want a return to casual sexism, smoky buses or three TV channels. But certain habits from that era can be surprisingly easy to adapt.

Families can, for instance, borrow two or three ideas without turning their lives upside down:

Set one or two evenings a week as screen‑light, conversation‑heavy time.

Give children small, regular chores linked to family life, not just to pocket money.

Plan simple joys – a park, a board game, a cheap cinema trip – and treat them as real events.

On a wider scale, urban planners and councils that invest in parks, libraries and safe streets are, in effect, rebuilding some of the community and outdoor freedom that earlier generations took for granted. Small policies, such as supporting youth clubs or intergenerational projects, can revive that sense of shared responsibility that once ran through many neighbourhoods.

For individuals, there is also a more private lesson. People who learned patience, thrift and resilience as children often draw on those skills decades later when facing illness, caring for ageing parents or dealing with job loss. Those traits do not erase difficulty, but they change the story from pure crisis to challenge.

The generation who grew up amid flared trousers, protest songs and rotary phones did not receive a perfect upbringing. Yet many of the quiet lessons they absorbed – about effort, time, family, community, nature and being honest about who you are – still speak sharply to a fast, distracted, anxious age.