The Antarctic coast looked like a jagged heartbeat on the ship’s control screens. White cliffs, black water, and a darkness that the cameras couldn’t get to. The engineers whispered as a small green dot blinked on the map. It was a robot the size of a small car that was floating silently under one of the biggest glaciers on Earth.

It had been alone under the ice for eight months, just listening.

One scientist stopped talking when the signal finally came back up through kilometres of frozen silence. The numbers on her laptop were quiet and shy. But everyone in the small lab knew what they were looking at.

It was the kind of signal they had hoped they would never see.

A robot that was hiding, an ice ceiling that was getting thinner, and a signal that no one wanted

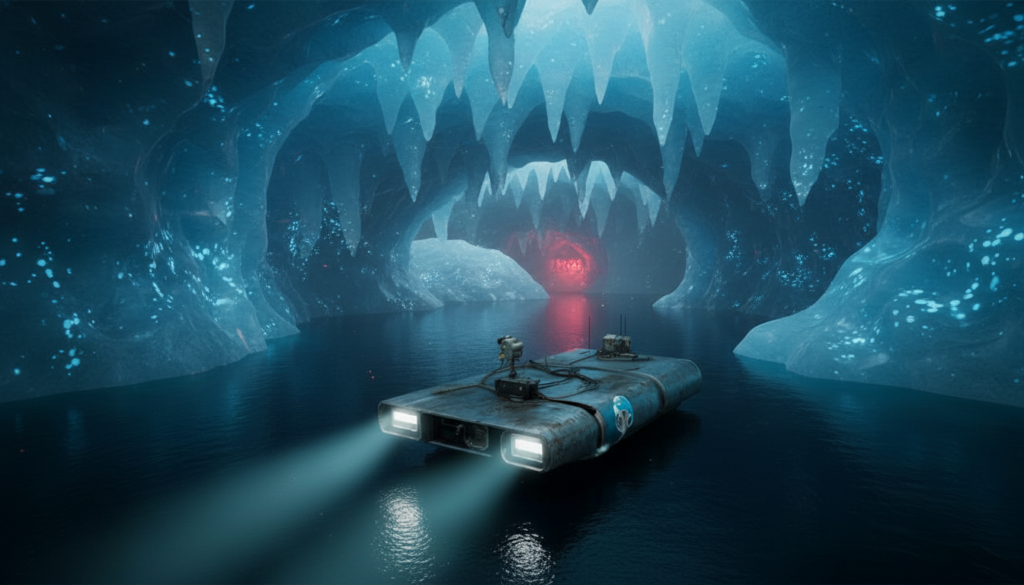

Icefin, the robot, didn’t look like a hero. It was a thin torpedo full of cameras, sensors, and a nervous system made up of wires and boards. It was launched through a hole in the ice and fell into the dark water below the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica, which is known as the “Doomsday Glacier.”

The surface up there looked like it would last forever. The robot found something very different down there. Warm ocean water slowly ate away at the ice, making it scalloped and cracked. Small changes in temperature and salinity made it clear that this glacier is not as stable as we had hoped.

The story of that robot’s eight-month drift is like a slow-motion thriller. Icefin moved under ice that was as high as skyscrapers, mapping the bottom of a frozen giant that holds back enough ice to raise sea levels by more than half a metre.

It measured small currents coming in from the deep ocean that were a little warmer and saltier than the water above. Those currents slid right up to the ice base, like a hot breath under a door that was locked.

The data showed that melting was happening all over, not just at the edges. It was slowly moving under the glacier’s thickest and most important parts, which scientists once thought were safe.

The researchers had been quietly worried about this signal: it looks like Thwaites is moving from “slowly changing” to “potentially unstable.”

If the glacier’s grounding line keeps moving back, it can start a chain reaction. This is the point where ice stops resting on rock and starts to float. Ice moves faster. Fractures go farther. The glacier can’t hold on anymore.

*Once that process really gets going, it’s almost impossible to stop it in the short term.*

This isn’t a twist in a Hollywood disaster movie. It’s quiet physics, which is what physics does.

What this means for the rest of us, who are far away from the ice

All of this can seem abstract from a warm living room. A robot under a glacier on the other side of the world sounds like something you saw in a documentary you only half-watched while scrolling through your phone. Over the course of decades, sea level rise is measured in centimetres.

But the connection between that lonely machine under the ice and the front step of a house in Florida, Bangladesh, or Brittany is very clear. As Thwaites becomes less stable, the coastlines that are far away feel the effects.

A small change in Antarctica causes a thousand little changes in cities we know by name.

You can already see the first signs. On clear days, tidal floods are creeping deeper into Miami’s streets. Saltwater is pushing up into wells on Pacific islands. Insurance companies are quietly raising premiums or not covering certain zip codes.

Researchers think that if Thwaites goes into a big retreat, it could eventually cause the sea level to rise by as much as 60 centimetres around the world. That’s in addition to what other glaciers and the warming oceans are already adding.

On paper, a few centimetres might not seem like a big deal. On a flat coastal plain, those centimetres make the difference between a storm surge staying outside or coming into the living room.

It’s not just “more melting” that the robot found under Thwaites. It’s a pattern of warm water getting into channels and cracks and hitting places that were thought to be safe.

This undercutting melts the ice from the bottom, making it thinner and making long, hidden holes. As the grounding line moves inland along a sloping seabed, more ice is exposed to the ocean. The system starts to make itself stronger.

Let’s be honest: no one really worries about grounding lines and basal melt rates while eating breakfast. But these are the quiet gears that turn behind the news stories about housing bubbles on the coast, migration, and decisions about infrastructure worth trillions of dollars.

How scientists read the ice and how you can use this information

Scientists’ methods for figuring out what that Antarctic signal means are almost like those used in criminal investigations. They don’t just freak out when they see one number. They put together temperature profiles, layers of salinity, sonar maps of the ice, and GPS records of how quickly the glacier is sliding.

Researchers drop CTDs, which are long frames of sensors, from ships to make vertical “fingerprints” of the ocean. Robots like Icefin add the last piece under the ice: a close-up of the handshake between the ice and the ocean.

They put together a moving, 3D picture of a glacier’s health, like a continuous MRI scan of a patient who can’t talk.

For the rest of us, that may sound far away from everyday life, but it happens in places we know well. That new ad for an apartment on the waterfront. The dream of a beach house for retirement. The political debate about rebuilding after yet another “once-in-a-century” storm that now seems to happen every ten years.

We’ve all been there: when a picture-perfect beach town feels like a paradise and a question mark at the same time.

It’s not about doomscrolling climate anxiety to know what’s going on under Thwaites. It’s about changing the stories we tell ourselves about safety, risk, and where we put our long-term roots and savings without making a big deal out of it.

When you talk to scientists who work on Thwaites in private, they are surprisingly straightforward. A lot of people have been watching this glacier for years, and some have even worked there their whole lives. The new signal doesn’t surprise them; it makes them feel even worse.

One glaciologist told a coworker, “Antarctica isn’t going to fall apart all of a sudden tomorrow.” “But some parts of it are now moving from the ‘maybe’ column to the ‘almost certainly’ column. We’re keeping track of the start of that change as it happens.

They often talk about a few real things people can do that are far away from the ice:

Before buying or fixing up a house in a low-lying area, check the local sea level projections.

Find out if your city has a plan for adapting to coastal changes or flooding. If it doesn’t, ask why.

When it comes to investments and pensions, keep an eye on how much exposure you have to coastal real estate and infrastructure.

Support policies that cut emissions this decade, not just by 2050. The first cuts are the most important for keeping the ice stable in the long term.

Stay curious: When you look at real data instead of just viral climate headlines, the future feels less like a vague threat and more like a set of choices.

A quiet alarm from the far south—and what we do with it

The strange thing about this story is that the moment of discovery wasn’t very dramatic at all. There were no alarms on the ship. There were no screams. A few people leaned in closer to the screens, wrote down numbers, pulled up old models, and compared them.

In that quiet, they realised that the glacier under their feet was changing shape faster than they had thought it would on their last trip. The robot had touched a future that is already starting, not waiting nicely for 2100.

Oceanographic charts don’t move as quickly as the rest of the world. Parents still hurry their kids to school, deliveries still come late, and rent still goes up. Antarctica feels like another planet in that background noise.

But there is a queue that connects the frozen emptiness and your bus stop. It goes through mortgage contracts, food prices, public budgets, new jobs in clean energy, changing coastlines, and the stories kids will hear about what their parents did in the 2020s.

The robot will be pulled back up through the ice, scratched and tired, with a lot of memories. New versions will come out after it, with better sensors, stronger code, and more tools.

These weak, constant signals will keep coming back from a world we don’t often see. The physics is already working on answering the question of what the ice will do. The real question is what we will do with the warning while we still have time to change the ending.

Main pointDetailValue for the reader

Thwaites The glacier is becoming unstable from below.Robot measurements show that warm water is getting to parts of the glacier’s base that were once safe.Helps readers understand why experts are worried about the sea level rising faster in the future

Risks of sea level rise are real, not just ideasEven small rises change how floods happen, how much insurance costs, and how much coastal property is worth.Gives readers a clear way to think about where they live, invest, or plan to retire.

Choices still matter for each personSmart local planning and early cuts to emissions can help lessen long-term effects.Gives you a sense of control instead of just worrying about the climate.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Question 1What did the robot under Thwaites Glacier find?

It recorded patterns of slightly warmer, saltier water reaching important parts of the glacier’s base, as well as signs of thinning and undercutting that suggest the ice-ocean system is becoming less stable.

Question 2: Why do people call Thwaites the “Doomsday Glacier”?

Scientists call Thwaites the “plug” because it holds back a lot of West Antarctica. If it collapses a lot, it could cause sea levels to rise a lot and change coastlines all over the world.

Question 3: Does this mean that cities will be underwater tomorrow?

No. Changes at Thwaites happen over hundreds of years. But the choices we make this decade about emissions, planning, and building will determine how bad or easy those changes will be in the future.

Question 4: What does this mean for people who don’t live near the ocean?

As the seas rise, they affect ports, global trade, food supply chains, and how much the government spends on infrastructure. People who live inland can also feel the social and economic effects of problems on the coast.

Question 5: Is there any good news in this study?

The good news is that clearer data leads to better predictions. If people know earlier that parts of Antarctica are moving, they have more time to change their ways, cut down on emissions, and avoid the worst possible outcomes.